It handled more payments last year than Mastercard, controls the world’s largest money-market fund and has made loans to tens of millions of people. Its online payments platform completed more than $8 trillion of transactions last year — the equivalent of more than twice Germany’s gross domestic product.

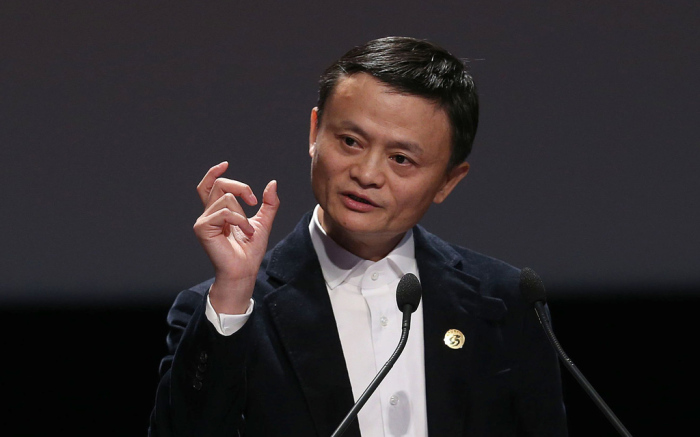

Ant Financial Services Group, founded by Chinese billionaire Jack Ma, has become the world’s biggest financial-technology firm, driving innovations that let people use their phones for buying insurance as easily as groceries, enabling millions to go weeks at a time without using physical cash.

That success is also putting a target on the company’s back. China, even more than the U.S., is now under pressure to reckon with the disruptive power of a financial-technology giant.

China’s banks complain Ant siphons away their deposits, causing them to pay higher interest rates, and is a factor leading them to close branches and ATMs. One commentator at a state-owned television channel described Ant’s huge money-market fund as “a vampire sucking blood from banks.”

Chinese authorities, clearly increasingly uncomfortable about Ant’s scale, have started to put limits on the activities it can pursue. Earlier this year, China’s central bank undermined a years-long effort by Ant to build a national credit-scoring system. The bank effectively prevented Ant’s system from being used by institutions making loans.

Regulators have issued rules requiring large money-market funds to sharply reduce holdings of assets that allow them to pay high interest rates. They have pressured Ant to slow inflows into its giant money fund.

The authorities are also weighing whether to designate Ant a financial holding company and require it to meet bank-style capital requirements, people familiar with the matter say. That would likely affect its profits, which last year came to $2 billion, pretax, on roughly $10 billion in revenue.

Investors remain spellbound, rewarding privately held Ant in June with a $150 billion valuation on paper, more than twice its valuation in a 2016 funding round and above that of Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

For years, Chinese authorities “turned a blind eye and let them grow as large as they could,” said Zhu Ning, deputy director of the National Institute of Financial Research at Tsinghua University, who says he has talked with regulators about risks to the financial system posed by Ant. “It is simply incredible that such a gigantic financial institution has slipped away from a comprehensive regulatory framework,” Mr. Zhu said.

The vice governor of China’s central bank, without specifying a company, recently warned that some influential payment institutions shouldn’t think of themselves as “too big to be regulated.” The central bank didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Ant executives reject the notion their company is acting like a bank without oversight. They say they are simply bringing financial services to people the banks have ignored.

They note Ant doesn’t fund most of the loans it originates from its own balance sheet. Instead, it largely serves as a platform that makes it easier for banks and others to extend loans and helps them lower risks.

“I don’t think banks see us as a disrupter,” said Leiming Chen, Ant’s general counsel. “We complement them and are helping them reach more customers.”

Chinese regulators, he said, “understand what we are doing and they are supportive of our efforts.”

Ant is expanding its presence overseas by getting more retailers to accept payments using its online payments service, Alipay, but has struggled to replicate its China business success. Early this year, Ant called off a takeover of U.S. money-transfer firm MoneyGram International after an American national-security panel refused to approve the acquisition.

In China, increased oversight of Ant and its competitors could hold back a golden age of financial-technology growth and indicate just how much change the country’s regulators will tolerate before stepping in to protect incumbents.

In recent months, fintech startups backed by Chinese internet companies such as e-commerce platform JD.com and search engine Baidu Inc. have pledged to move away from directly offering financial services and toward providing platforms for traditional institutions to use.

Ant is doing the same. It says it wants to be known not as a financial conglomerate but as a technology provider or “lifestyle platform,” with future profits coming mainly from fees from institutions using its technology.

Such strategy shifts are common in China when “the state advances,” said Carson Huang Mihan, a former Ant executive and the founder of a fintech firm called Camel Financial.

Consumers such as Elaine Wang show Ant’s power. The 30-year-old Shanghai marketing manager transfers about a third of her salary from her China Merchants Bank account into Ant’s investment products and uses Alipay several times daily for simple transactions such as buying coffee.

More than 620 million people use Alipay, a person familiar with the number said. Once people’s money moves from conventional bank accounts into their virtual wallets, much of it doesn’t return.

In Hangzhou, Ant occupies a glass-walled, Z-shaped complex designed by the firm behind Amazon.com’s new Seattle offices. Employees are greeted by a tall red sculpture of a naked man bent down looking at the ground.

Digital cameras scan many employees’ faces as they enter. Meeting-room booking rules say anyone can take over a space if users don’t show up within a minute of their allotted times.

Virtually everyone in the company uses an alias, a tradition inherited from Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., the e-commerce goliath from which Ant emerged.

Many names are inspired by kung fu novels, which Alibaba’s Mr. Ma likes, and reinforce a general absence of hierarchy. Some employees don’t know colleagues’ real names. They are told they can pick aliases because they couldn’t choose their names at birth.

Mr. Huang, the former Ant executive, recalls a company where the average age was under 27 and some employees had worked at Mastercard, PayPal and foreign banks. “It was a place full of young, idealistic financial elites, many of whom had studied abroad,” he said.

Ant’s roots trace to 2004, when Alibaba created Alipay to smooth online shopping. Alibaba has a popular eBay-like service called Taobao that connects buyers with third-party sellers. It needed a secure and reliable way to send payments.

Mr. Ma wasn’t bothered that China didn’t have a regulatory structure for a nonbank payment company. “If someone needs to go to jail for this product, I will go,” he told colleagues, alluding to the legal gray area. Mr. Ma couldn’t be reached for comment.

As Alipay grew, its executives realized they could push the financial system to change. Mr. Ma said in December 2008 that China’s banks weren’t doing enough to support small businesses. Large banks did much of their work with state-owned enterprises, ignoring small firms that could use more capital.

“If the banks do not change, we will change the banks,” Mr. Ma pledged at an entrepreneurship conference that year. An Alibaba unit later began making loans to some small businesses.

In 2010, Mr. Ma carved Alipay out of Alibaba after authorities said the payment operation would need a new license to operate.

By 2013, Alipay was holding billions of dollars of customer funds in escrow, a custodian bank account, for transactions on Taobao. Even then, executives worried banks would see Alipay as a competitor, recalls a former employee, as it accumulated piles of money and made plans to offer more financial services.

Employees came up with the idea of letting customers stash their idle Alipay money in an online money-market fund to earn income. The fund, known as Yu’e Bao, or “leftover treasure,” allows Alipay users to invest as little as 0.01 yuan ($0.0015) and to transfer cash in and out without fees.

More than a million people shifted money into the fund within days of its launch in June 2013, drawn by yields several points above what banks paid on short-term deposits. Yu’e Bao generated returns by investing in high-yielding products riskier than those banks were allowed to tap.

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the country’s biggest bank by assets, responded to the instant popularity of the money-market fund by sharply reducing the amount Alipay users could withdraw in a single transaction. Other banks also tightened limits.

Yu’e Bao was a blow to banks because it sucked money from savings accounts, said Ma Weihua, then-chairman of Wing Lung Bank, in 2014. Some banks issued commercial paper to Yu’e Bao, incurring higher costs of funding.

By then, Jack Ma had stepped down as Alibaba’s chief executive (remaining chairman), and in 2014 Alipay rebranded itself as Ant. Executives outlined plans to expand into personal loans, small-business lending, credit scoring and insurance. The company would take advantage of China’s rapid adoption of smartphones.

Then came the backlash. Last summer, the company kicked off a campaign in the city of Wuhan to promote a “cashless society.” It offered Alipay users rebates encouraging them to pay in stores with mobile phones.

Days before the official launch, Ant refashioned the campaign after officials from a local office of China’s central bank asked it to remove the word “cashless” and told store owners not to reject cash, according to the state-owned People’s Daily newspaper. The central bank later denied having issued the order, according to another state-owned news service. The bank didn’t respond to requests to clarify its position.

In September, Chinese securities regulators said that some large money-market funds were “systemically significant.” Without naming Yu’e Bao, regulators issued rules requiring large money funds to reduce holdings of their hard-to-sell assets. Ant’s asset-management unit announced measures to limit inflows into Yu’e Bao and committed to paring its holdings of longer-term and riskier securities.

A few months later, China’s central bank struck a blow against Ant’s credit-scoring system, Zhima Credit, known in English as Sesame Credit.

Unlike the U.S., China has long lacked comprehensive nationwide credit-scoring, considered essential to a consumer economy. In early 2015, the central bank encouraged Ant and several other private companies to develop their own credit-rating systems.

Ant was quick off the mark, bringing out a system that uses numerous variables including people’s payment history on Alipay.

In the spring of 2017, a Chinese central bank official said at a seminar that credit scores created by private companies were “far below qualification.” And this year, the central bank licensed a new state-owned company, Baihang Credit Scoring, to create a nationwide credit-scoring system.

Ant’s Mr. Chen said the company now uses its Zhima Credit only for services such as waiving deposits for bicycle rentals for people with high scores.

“The ambition of Zhima Credit was never to build a nationwide credit scoring system or to service financial institutions for a fee,” a spokesman said.

Recently, the central bank required nonbank payment operators such as Alipay and its chief rival WeChat Pay, operated by Tencent Holdings Ltd., to place escrow funds in non-interest-bearing bank accounts by early 2019, to prevent misuse. That means they won’t be able to use escrow money to generate interest gains.

Partly as a result, online-payment services, which provided 65% of Ant’s revenue in 2016, are expected to provide less than a third of it in 2021, said a person familiar with the matter.

Ant is also being told to cede control over some of its transaction data to a new, government-owned internet payment system called Wang Lian, which is expected to compete against Ant and could undercut it on fees, people familiar with the matter said.

Some investors in Ant say they aren’t concerned. “The intent of the Chinese regulators was never to stifle its growth,” said Ben Zhou, a managing director at U.S. private equity firm Warburg Pincus. His firm was among global investors that recently pumped $14 billion into Ant. Ant is unlike any company in the world, Mr. Zhou said. It is “a whole new species.”