Whether you think Facebook is a formidable business, a great place to find old school chums, or a terrific waste of time, it is ultimately just a moment in the long evolution of the internet. And its moment will pass.

The internet has a way of breaking established orders. Time was, people who wanted to congregate fished start-up disks from their junk mail, got dial-up modems, and went to America Online. Then came the world wide web, and it was suddenly cool to have one’s own website. AOL was toast. Then a smart fellow named Mark Zuckerberg developed a website where the whole world could congregate and called it Facebook (ticker: FB).

Then came the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the alleged manipulation of information on Facebook by foreign actors, and last week’s 10 hours of Zuckerberg testimony before Congress. A key question in those hearings was how anyone could trust a central database containing everything about a person.

The first line of Facebook’s terms of service, as Zuckerberg repeatedly told Congress, is that you own your personal information, though recent news calls that assertion into question.

Facebook may not yet have reached its AOL moment, but it will come. It’s too soon for venture-capital money to pour into start-ups looking to replace Facebook, but the ingredients of a new social network are bubbling up. “We are seeing the beginning of a major wave of interest in something that has no central authority, where everyone is participating in a system that no one person owns,” says Leonard Kleinrock, a professor at UCLA and one of the inventors of the internet.

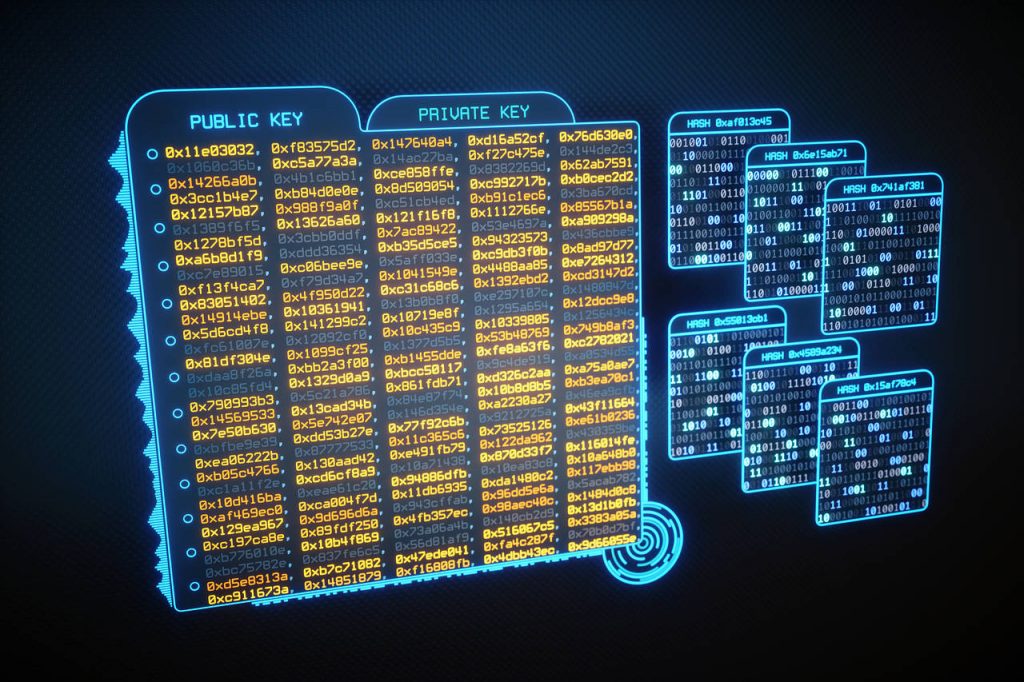

Kleinrock is working with a company called Sunday Group on a project where people form groups based on shared interests such as music or cuisine, and recognize and reward one another for expertise. His work relies in part on blockchain, the technology underlying the cryptocurrency called Bitcoin. Blockchain has qualities you would want in a new social network. It is decentralized, with no single party owning the database of information. And each participant in blockchain can control their own assets, including their personal information.

In a blockchain world, any business wanting to make money showing ads against personal information couldn’t just appropriate the information, like Facebook does. The business would have to formally transact with the individual to obtain use. That’s what you call “opting into” the system, versus Facebook’s “opt out” reality.

Facebook is where people go to feel connected, and anything displacing it would probably need to have that same “network effect.” Robert Metcalfe, one of the inventors of the Ethernet networking technology, first proposed the idea that the value of a network increases at a rate equivalent to the square of the number of entities participating. That has come to be known as Metcalfe’s Law. Facebook, Metcalfe told Barron’s, “is the Metcalfe’s Law company.”

Recent research has shown that blockchain has network effects that agree with Metcalfe’s Law: The more people who use blockchain, the more it takes on a kind of runaway popularity.

But there are problems. Blockchain’s viral quality has come from speculators in Bitcoin and other currencies, which could blow away like the proverbial tulip. And unlike the Web, blockchain isn’t easy to use. Those faddish devotees have to buy computers with expensive graphics chips from Nvidia (NVDA) or Advanced Micro Devices (AMD).

More concerning: Whatever information is put into blockchain remains there forever. Those embarrassing photos of you last night? Unlike Facebook, you wouldn’t be able to delete them from blockchain, or else the system’s integrity is violated.

“In theory, blockchain could form a social network, but in practice, probably not,” says Tim O’Reilly, a legendary tech observer and CEO of O’Reilly Media. “I’m skeptical of me-too applications. It cannot be some version of what exists, it would have to be some fundamentally new thing.”

Open-source software such as Linux, O’Reilly says, didn’t dethrone Microsoft (MSFT) by being a decent replacement. Open source won because “it became the foundation for new internet services and applications that had completely different rules.”

Any replacement of the social network might require some kind of bold new user interface, such as virtual reality. That’s why Zuckerberg bought VR startup Oculus, notes O’Reilly, as a hedge against the future.

Kleinrock says his work on reputation systems can offer something new in social. “The trick is to have domains [of mutual interest] where you already have some recognized curators,” he says. “If you are passionate about music, and you follow people who are very involved in music, you would be happy to engage with them, and possibly to reward them” with some kind of monetary remuneration for their expertise. He hopes the effort will dispel misinformation such as fake news.

The generation growing up today is “used to interacting with and referring things without a central authority,” Kleinrok adds. “They respect and recognize sources that are accurate on a regular basis, wherever they find them.”

Bulls on Facebook stock can take heart in the fact that displacing the Social Network is a daunting prospect. “It’s not to say Facebook will never be replaced, but I think it’s very unlikely until we see the next major user interface,” O’Reilly says.

But the internet is rapacious. It jumps on successful ideas, reconstitutes them in a new form, and dethrones the old order. It can take years to happen, but when it does, a big reason is the old guard’s Achilles’ heel, a tendency to overstep its bounds, and break trust with society.