A chief strategist of Venezuela’s government-backed cryptocurrency is a former U.S. congressional intern who once organized protests against the same socialist administration he’s now helping to circumvent U.S. financial sanctions.

Gabriel Jimenez, 27, was catapulted to something of tech stardom in Venezuela last month when he stood alongside President Nicolas Maduro and two Russian businessmen on national TV signing a contract to position the petro, as the fledgling currency is known, among international investors.

“It’s a company founded and led by young Venezuelan geniuses, boys and girls of Venezuela, who have one of the most technologically advanced blockchain companies in the world,” a beaming Maduro said at the petro’s unveiling, referring to Jimenez’s company, The Social Us.

It was a remarkable reinvention for Jimenez.

Maduro has repeatedly hailed the petro as a way to “overcome the financial blockade” by the Trump administration that prevents his cash-strapped government from issuing new debt. But Jimenez until recently had been agitating for the very same actions to punish Venezuela’s leader for jailing his opponents and destroying the oil-rich economy.

A lawyer by training who describes himself as an “innovation enthusiast,” Jimenez spent several years working at a Dominican Republic-based bank where his father was a top manager. The bank collapsed in 2014 and his father was among several Venezuelan executives charged by the Caribbean nation with defrauding depositors of $30 million.

After college Jimenez also started traveling to the U.S. for English and summer graduate classes at Harvard and George Mason Universities. In 2013, he started The Social Us, registering the company in Florida, as a webpage and app developer.

In 2014, Jimenez worked five months as an intern in Washington for Miami Republican Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, one of Maduro’s fiercest critics. A handwritten survey he filled out upon being hired, a copy of which was provided by her office, listed in broken English that his goals for the internship were gaining “knowledge and experience about the defence of democracy.”

Colleagues remember him as a spirited anti-government crusader who helped organize a caravan, known as the Trip For Freedom, in which thousands of Venezuelan exiles traveled by bus to Washington to pressure the Obama administration to slap sanctions on Maduro’s government. In photos of the event, he can be seen standing on a podium with Ros-Lehtinen at the Capitol addressing supporters in front of an American flag and photos of Venezuelan students allegedly tortured by security forces.

Now his former boss thinks he or anyone else behind the petro should be considered for sanctions too.

“Gabriel came to our office and said he wanted to learn how to support freedom and democracy,” Ros-Lehtinen said in a statement. “Instead, it appears he is using the freedoms that the United States provided him in order to help advance the Maduro regime’s attempts to consolidate power and destroy Venezuela’s democratic institutions. Those who work to support the Maduro regime and provide it a financial lifeline have chosen their lot and should expect to face the full consequences of turning against their people.”

Jimenez in an interview defended his work for the government as serving a greater, non-political purpose: to empower Venezuelans struggling to feed themselves amid four-digit inflation.

He said his work on what would become the petro began when he returned to Venezuela in 2015 and banded together with other tech entrepreneurs to design a digital currency. The group then looked to partner with the government in the hopes of bringing Venezuelans’ underground trading in cryptocurrencies out from the shadows and into legal circulation. At the time, bitcoin miners faced the threat of arrest or extortion by government agents.

If the petro takes off, he says, Venezuelans will be able to freely exchange their worthless bolivars for a more stable currency, giving them a chance to raise capital and save. Currently the only way for the majority of Venezuelans to get around strict currency controls imposed in 2003 is to buy hard currency in the illegal black market.

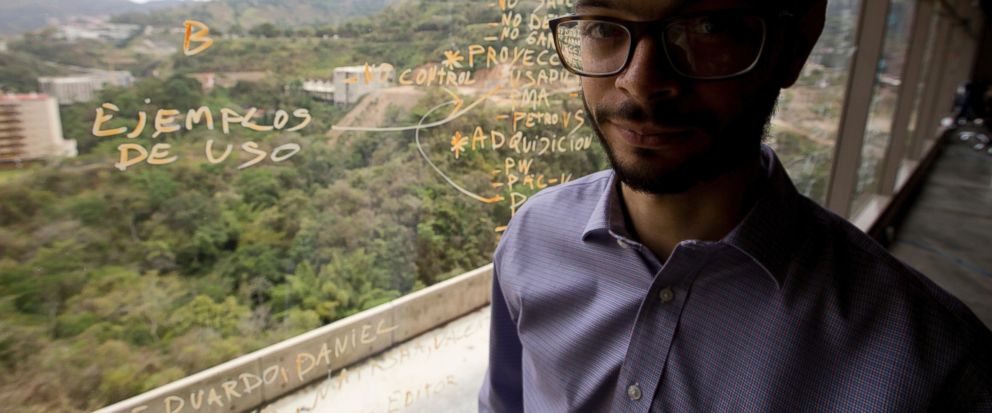

“This is about providing oxygen to people, not a government,” Jimenez said in an interview at the bustling Caracas office of The Social Us, where a dozen young programmers scrawled code in pink markers on glass windows overlooking a verdant valley and busily designed promotional materials for the petro.

It’s a trade-off that many in Venezuela’s burgeoning blockchain community — almost all of them ideologically opposed to the government — are willing to accept.

Still, there’s no denying the government will be the first and perhaps biggest beneficiary.

This month, Maduro said the government had received commitments from investors to purchase $5 billion worth of the cryptocurrency during the pre-sale phase that culminates this week. If those materialize into actual sales, it would be a windfall equivalent to more than half of Venezuela’s dollar reserves — money the government is desperately clutching onto as it juggles re-paying billions in defaulted bonds while trying to eradicate widespread shortages.

However, members of the U.S. Congress are pushing for a robust response, fearing that other nations under U.S. sanctions such as Iran and Russia could emulate Venezuela’s example, or that the petro could be used by criminal networks or corrupt officials to launder money.

Of the two Russians who also signed agreements with the government to help develop the petro one, Denis Druzhkov, CEO of a company called Zeus Trading, was fined $31,000 and barred from trading for three years by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange for fraudulent trading in futures’ contracts. The other, Fedor Bogorodskiy, lives in Uruguay and was described by the government as director of a company, Aerotrading, whose website consists of a single home page with no company information.

Neither would comment on their work with the Venezuelan government. But in response to the request for comment, an email signed by “Zeus Team” said that Druzkhov had been invited to Venezuela as an expert and Zeus is not working on the project. It also said that as part of Druzhkov’s settlement with the Mercantile Exchange in 2014, he did not admit to any rule violations.

Sens. Bill Nelson and Marco Rubio of Florida and Bob Menendez of New Jersey are calling on the Treasury Department, which is responsible for enforcing sanctions, to combat use of the petro so it’s not used to circumvent a ban against Americans lending money to Maduro’s government.

The Treasury Department said in January that the petro would appear to an extension of credit to Venezuela and warned all U.S. persons that “deal” in the digital currency may risk falling afoul of U.S. sanctions.

Jimenez, whose preference for sneakers and jeans exude a sort of nerd aesthetic not unlike his entrepreneurial role models in Silicon Valley, said he never intended to help circumvent U.S. sanctions. He also argues that the petro — a financial product that doesn’t generate interest or have a payback schedule like a bond — doesn’t qualify as the sort of debt instrument the Trump administration is targeting.

Instead, he talks of “democratizing” access to global financial system for struggling entrepreneurs and decentralizing Venezuela’s government-run foreign exchange system, which many blame for the economy’s depressed state.

“We can’t just sit here with our arms crossed, with all that we, our friends and our family are going through,” he said. “Doing nothing would be irresponsible.”